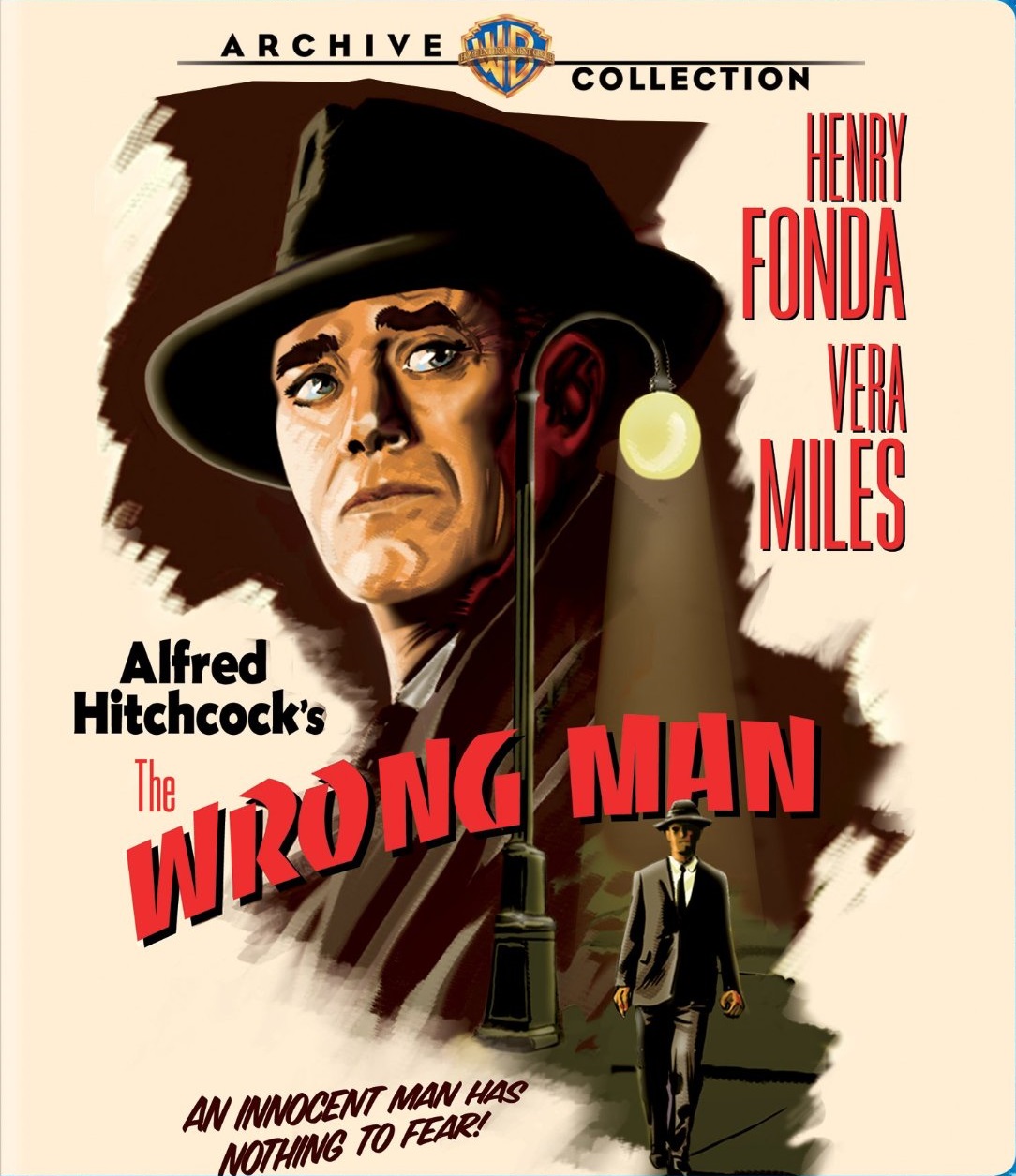

Distributor: Warner Bros.

Release Date: January 26, 2016

Region: Region A

Length: 01:45:20

Video: 1080P (MPEG-4, AVC)

Main Audio: English 2.0 DTS-HD Master Audio

Alternate Audio:

2.0 French Dolby Digital

2.0 Spanish (Castellano) Dolby Digital

2.0 Spanish (Latino) Dolby Digital

Subtitles: English SDH, French, Spanish (Castellano), Spanish (Latino), Czech, Polish

Ratio: 1.85:1

Bitrate: 32.91 Mbps

Notes: This title was previously released and is still available in a DVD edition.

“On about 5:30 on the evening of last Jan. 14 a 43-year old nightclub musician named Balestrero mounted the steps of his home, a modest stucco two-family house at 41-30 73rd St. in Queens, a borough of the City of New York, and took out h. is key. As he did so, he heard a hail from across the dark street: ‘Hey, Chris!’ Balestrero turned curiously. His first name was Christopher, but he is known to his family and friends as ‘Manny,’ a shortening of his middle name Emanuel. Three men came up to him out of the murky shadows of a winter evening. They said they were police officers and showed him badges clipped to wallets.

Balestrero, experiencing a little quiver of uneasiness, asked what they wanted. The detectives ordered him to come to the 110th precinct station. They were polite, firm and uninformative. Balestrero became alarmed… His conscience was clear, and the detectives were polite, but their inexorable manner was frightening.

Without even going in to tell his wife that he had returned from an afternoon visit with his mother in Union City, N.J., Balestrero accompanied the three detectives to the precinct station, and then on a tour of a dozen Queens liquor and drug stores and delicatessens. At each stop, the routine was the same. Balestrero was instructed to go into the store and walk to the counter and back under the scrutiny of the proprietor. As they drove between stores, the detectives talked with Balestrero of inconsequential things like television programs. They assured him that if he had done nothing he had nothing to fear.

On their return to the station the detectives told him what it was all about… Up to this point the train of events had the somnambulistic quality of a bad dream. Now it became a nightmare.” -Herbert Brean (A Case of Identity, Life Magazine, June 29, 1953)

It is easy to picture the portly director with a twinkle in his eyes as he read Brean’s text. As a matter of fact, one might mistake these paragraphs for a rough treatment outline for the eventual screenplay. This isn’t the case at all. “A Case of Identity” was simply an article about a tragic mistake that nearly ruined a man’s life. It was merely a coincidence that it touched upon some of Alfred Hitchcock’s pet themes. Herbert Brean was, however, commissioned to work with the director on a 69 page treatment in the June of 1955.

Actually, the article was adapted as the subject for an 60-minute episode of “Robert Montgomery Presents” in 1954, but the episode was nowhere near as chilling (or as brilliantly rendered) as Alfred Hitchcock’s film. He remained faithful to the facts contained in Brean’s article, and even did exhaustive additional research into the case in order to ensure fidelity to Balestrero’s unique story. Hitchcock became consumed with minute details, and this concern can be seen in the final product.

As a matter of fact, Hitchcock had been secretly longing to make a more down-to-earth story (having been inspired by Italian Neo-realist films). Balestrero’s story seemed the perfect subject for him to achieve this goal.

“The Wrong Man offered Hitchcock a real-life incident—involving an Italian American—that would enable him to continue his lifelong critique of the judicial system. It gave him an opportunity to adopt an ‘unmistakably documentary’ approach, in his words—a radical challenge for the director… He wanted to tell the story exactly as it had transpired, with minimal dramatic or cinematic embellishment.” -Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Hitchcock himself elaborated on the film’s fidelity to the actual events in great detail during his lengthy interview with François Truffaut years later. He even gave a specific example:

“…For the sake of authenticity everything was minutely reconstructed with the people who were actually involved in that drama. We even used some of them in some of the episodes and, whenever possible, relatively unknown actors. We shot the locations where the events really took place. Inside the prison we observed how the inmates handle their bedding and their clothes; then we found an empty cell for Fonda and we made him handle the routines exactly as the inmates had done. We also used the actual psychiatric rest home to which his wife was sent and had the actual doctors playing themselves.

But here’s an instance of what we learn by shooting a film in which all scenes are authentically reconstructed. At the end, the real guilty party is captured while he’s trying to rob a delicatessen, through the courage of the lady owner. I imagined that the way to do that scene was to have the man go into the store take out his gun and demand the contents of the cash drawer. The lady would manage in some way to sound the alarm, or there might be a struggle of some kind in which the thief was pinned down. Well, what really took place—and this is the way we did it in the picture—is that the man walked into the shop and asked the lady for some frankfurters and some ham. As she passed him to get behind the counter, he held his gun in his pocket and aimed it at her. The woman had in her hand a large knife to cut ham with. Without losing her nerve, she pointed the point of the knife against his stomach, and as he stood there, taken aback, she stamped her foot twice on the floor. The man, rather worried, said, ‘Take it easy, lady.’ But the woman, remaining surprisingly calm, didn’t budge an inch and didn’t say a word. The man was so taken aback by her sang-froid that he couldn’t think of what to do next. A;; of a sudden the woman’s husband, warned by her stamping, came up from the cellar and grabbed the thief by the shoulders to push him into a corner of the shop against the food shelves while his wife called the police. The thief, thoroughly scared, began to whine: ‘Let me go. My wife and kids are waiting for me.’ I loved that line; it’s the sort of thing you wouldn’t dream of writing into a scenario, and even if it occurred to you, you simply wouldn’t dare use it.” -Alfred Hitchcock (Hitchcock/Truffaut)

Fidelity was probably the issue that Hitchcock, Angus MacPhail, and screenwriter Maxwell Anderson discussed most during the writing sessions. Minute details were discussed at length. No detail was too mundane for Hitchcock. He wanted to know how many people would have been in a subway station at 4 o’clock in the morning, what time a five-year-old would go to bed, precise police procedure, the order of events, and what the principal and ancillary participants in this real-life story were thinking and doing at every point in the story.

“When Anderson placed the scene where Manny is booked and fingerprinted too early in the script, Hitchcock gently reminded the writer of ‘the actual order of events.’ When Anderson wrote a speech in which a juror interrupted the proceedings to admit he has already reached a guilty conclusion before hearing all the evidence, Hitchcock praised Anderson’s writing, but said he couldn’t use the speech in the film. Anderson had taken too much license, and the speech as written was fictitious—‘a major contradiction of the actual events, and could be so easily used in hostile criticism.’ Whenever the team hit a dry spell, they returned to the actual people. Re-interviewing them for new ideas.” -Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

This isn’t to say that minute details weren’t slightly altered for structuring purposes (or for points of clarity). There were small changes made if they could be altered without betraying the overall reality of any given moment. Of course, the biggest change made from the actual events was the text-based epilogue that was added to the final shot that assured audiences of Rose’s recovery. Rose had not fully recovered at the time the film was released. Audiences of the era expected happy resolutions.

Hitchcock has also been criticized for including a scene that shows the real culprit incriminating himself just as Manny begins to pray, but Balestrero’s strong catholic faith was suggested in the Brean article more than once. (In fact, Hitchcock discovered that Manny’s mother did urge her son to pray for strength after the mistrial.) The first suggestion of his faith in prayer occurred while Manny was waiting in a small jail cell.

“…He could not sleep. A religious man, he spent most of the night in prayer, much of it on his knees. He wondered what would happen to him…” -Herbert Brean (A Case of Identity, Life Magazine, June 29, 1953)

The next example is even more suggestive (and is also dramatized in Hitchcock’s film version).

“…The first girl was asked I the holdup man was in the courtroom and, if he was, to step down and place her hand on his shoulder. The girl pointed out Balestrero, but when she tried to touch his shoulder she almost fainted from fear. It obviously impressed the jury. After that, the other girl witnesses were asked to point him out, and one after another they did. Balestrero again was seized with a wild desire to stand up and shout. ‘It’s a horrible feeling, having someone accuse you. You can’t imagine what was inside of me. I prayed for a miracle.

And a miracle—of sorts—happened. On the third day of the trial Juror No. 4, a man named Lloyd Espenschied, rose suddenly in the jury box… ‘Judge, do we have to listen to all this?’ The question implied a presupposition of the defendant’s guilt by a juror—a violation of his responsibility to refrain from any conclusion until all the evidence is in. It gave the defense an opportunity to move for a mistrial…” -Herbert Brean (A Case of Identity, Life Magazine, June 29, 1953)

It isn’t a huge stretch to assume that the stress of having to go through the process of another trial would lead to more prayer. This is an established habit of the real-life Manny. In light of this, it seems that those who have criticized this particular scene are merely nitpicking.

In an article published in a 1957 issue of Cahiers du Cinéma, François Truffaut had compared The Wrong Man favorably to Bresson’s A Man Escaped (Un Condamné a Mort s’est échappé). He even went as far as to say that the film “is probably his best film, the one that goes farthest in the direction he chose so long ago.” However, his opinion seems to have changed somewhat in the decade that followed. In his 1966 interview with Hitchcock, Truffaut suggested that the film suffered because “the esthetics of the documentary” was in conflict with Alfred Hitchcock’s signature subjective style. He uses the moment where the camera spins around Henry Fonda in his cell as an example. This seems an unfair statement, because the power of The Wrong Man comes from Hitchcock’s subjective treatment. The story certainly has a dramatic power on its own, but the subjective treatment makes the audience feel as if they have been personally violated in the same manner that Manny Balestrero was violated (and it does this without taking away from the film’s authenticity).

One of Alfred Hitchcock’s more annoying personal idiosyncrasies was his habit of adopting the prevailing critical opinion about his films. This certainly seems to be the case here. Since The Wrong Man wasn’t the giant hit he had become accustomed to, he deemed the film a failure and tried to remove himself from it as much as possible in interviews. After Truffaut’s criticism, he responded with the following:

“The industry was in a crisis at that time, and since I’d done a lot of work for Warner Brothers, I made this picture for them without taking any salary for my work. It was their property.” -Alfred Hitchcock (Hitchcock/Truffaut)

It is true that the director made the film without taking a salary, but analytical minds must question whether Hitchcock did this purely out of kindness to the studio. After all, Warner Brothers owned the film rights to Balestrero’s story. It seems quite possible that Hitchcock’s decision could have stemmed from a sincere personal desire to adapt that property into a motion picture. It seems likely that Hitchcock is merely distancing himself from the film due to Truffaut’s negative commentary. There is a passage in Patrick McGilligan’s biography of the director that seems to support this theory:

“Warner’s was actually ambivalent about The Wrong Man until Hitchcock offered to waive his salary, an offer calculated to win him the go-ahead to make the picture. It’s hard to think of very many other directors in Hollywood history who have volunteered to work for free this way, at the peak of their success. Yet such a director was entirely in character for Hitchcock, who had often ignored money to make the films that interested him.” -Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

The director had other complaints about the film in the years that followed the film’s release. The most notable of these concern the character of Rose Balestrero. Hitchcock claimed that he felt that Manny’s story collapsed when Rose’s mental faculties began to deteriorate, and he often cited this as one of the film’s weaknesses. On the contrary, Rose’s breakdown is what carries the story to the trial. It has the effect of keeping the audience with Manny, and it is one of the most interesting things about the film.

The most poignant scenes are those that concern Rose, and we never feel Manny’s pain more than when he is worried for his wife. A perfect example is a scene that seems to have been plucked from the Brean article:

“…There Balestrero confronted the man who more than anyone else was responsible for his 15 weeks of torment. Daniell was handcuffed to a chair. He looked up at Balestrero once and did not look again. There was a fleeting resemblance between the two men, particularly in the set and expression of their eyes. Balestrero asked, ‘Do you realize what you have done to my wife?’ Daniell did not answer.” -Herbert Brean (A Case of Identity, Life Magazine, June 29, 1953)

Let there be no mistake that these elements carry the audience through to the end of the film in a way that would have been nearly impossible to achieve otherwise. Frankly, this seems to be yet another scapegoat utilized to help Hitchcock distance himself from the film in the public’s mind. The root of this criticism probably stems from a number of reviews that suggested that Rose’s story was one of the film’s weaker elements. One such review was published in The Times:

“…In any event, the second half of the film, which sees Manny out on bail, hunting desperately for witnesses which will establish his alibi—while his wife, who is troubled with feelings of guilt, declines into apathy and eventually has to be sent to a mental institution, lacks the hypnotic fascination of the first.” -The Times (February 25, 1957)

It is simply another example of Hitchcock’s tendency to adopt critical opinion as his own. There isn’t any evidence that would suggest that Hitchcock walked onto the set feeling that this aspect of the script was deficient in any way. In fact, there is evidence to the contrary. The director had cast Vera Miles (who he had under personal contract) to play the role of Rose Balestrero, and he had spent a lot of time developing this aspect of the story.

On March 06, 1956, Alfred Hitchcock wrote the following to Maxwell Anderson:

“I have always personally felt (whether I am correct or not would be or you and Angus to say) that the scenes of the preparation of the defense should begin to be interrupted by an unexpected element, i.e. the decline of Rose, so that the mechanical details of alibis, etc. become obscured by this growing process o Rose going insane. So that by the time we reach the eve of the trial the drama of Rose has taken over.” -Alfred Hitchcock (as published in “Hitchcock and Adaptation: On the Page and Screen,” edited by Mark Osteen)

Not only did Alfred Hitchcock not mind that Rose’s story took over the narrative at this point, it was his intention that this happen. Without Rose’s breakdown, this part of the film would be rather dull. Hitchcock certainly realized this and added minor elements to the story to spice up the drama.

“…In this same letter, Hitchcock mentions another small but telling addition to the sequence in which the Balestreros hunt down witnesses who can testify that they were out of town during the first holdup. As the couple track down a witness by the name of La Marca, Hitchcock and MacPhail insert ‘two callous giggling teenagers’ announcing to Manny and Rose that the witness has died. Then the hapless Balestreros learn that a second witness, Mr. Molinelli, has also died. ‘There’s our alibi! Alibi! Oh, perfect! Complete!’ responds Rose. Anderson echoed Rose’s words, praising the insertion of the giggling girls and declaring that the scene was ‘beautifully handled.’ (Anderson to Hitchcock 03/17/56).” -Mark Osteen (Hitchcock and Adaptation)

Hitchcock’s tendency to disregard films that do not meet with overwhelming success does his work a grave disservice. Critical opinion has a way of evolving, and Hitchcock’s dismissal of The Wrong Man has made this evolution rather difficult. When he told Truffaut to “file The Wrong Man among the indifferent Hitchcocks,” he was giving future critics and scholars permission to do the same.

This is especially unfortunate considering that the unenthusiastic reviews that flooded newspapers, trade journals, and magazines upon the film’s release were colored by a rather narrow-minded expectation of what a Hitchcock film should be. The critics were conditioned to expect exciting films with a dose of macabre humor. The Wrong Man doesn’t deliver these elements. Instead, audiences experienced a deliberately paced emotional drama. The film’s sober tone was not what the critics wanted from Hitchcock. For example, a December 22, 1956 review published in Harrison’s reports complained that although Henry Fonda and Vera Miles were excellent in their roles, “stories about human suffering are, as a general rule, depressing, and this one is no exception…”

A.H. Weiler was similarly disenchanted with the film:

“The theory that truth can be more striking than fiction is not too forcefully supported by the saga of The Wrong Man, which was unfolded at the Paramount on Saturday.

Although he is recounting in almost every clinical detail startling near-miscarriage of justice, Alfred Hitchcock has fashioned a somber case history that merely points a finger of accusation. His principals are sincere and they enact a series of events that actually are part of New York’s annals of crime but they rarely stir the emotions or make a viewer’s spine tingle. Frighteningly authentic, the story generates only a modicum of drama…

…Mr. Hitchcock is not setting a precedent with The Wrong Man. Facts have provided fiction for many films before as in Let Us Live, in which Mr. Fonda also was starred. Mr. Hitchcock has done a fine and lucid job with the facts in The Wrong Man but they have been made more important than the hearts and dramas of the people they affect.” -A.H. Weiler (New York Times, December 24, 1956)

This seems to be a rather unfair conclusion on Weiler’s part, but one must remember the sort of film he was expecting. One wonders why his contemporaries dismissed him for not telling realistic and socially relevant stories only to become disappointed when he gives them such a film (as he certainly did with The Wrong Man).

Scholarly opinion hadn’t changed much when Robert A. Harris & Michael S. Lasky published a book of critical essays entitled, The Films of Alfred Hitchcock in 1976. Harris and Lasky seem to have taken a page from Alfred Hitchcock’s book, because they also singled out Rose’s story as the films primary weakness. It is worth questioning whether or not these men would have come to this conclusion had it not been one of Alfred Hitchcock’s repeated interview testimonies. Original ideas are rare (especially in film criticism). They were also quick to follow the lead of many critics that came before them in condemning Hitchcock’s climactic prayer scene.

“The Wrong Man has a newsreel quality to it, with starkly lit black-and-white photography and real-life details that give it authenticity. When Hitchcock switches gears and no longer emphasizes Christopher Balestrero’s story, turning instead to his wife’s, he loses the audience’s interest. The intensity of the drama, horrifying because of its reality, diminishes because the chief focal point has been complicated with more details than the audience wants to consider

It is precisely because of this twist in the plot, the focusing on Rose’s mental breakdown that explains why Manny turns to prayer at the end. He prays for a miracle. With double exposure, he superimposes the holdup man’s face over Manny’s as he is praying. The documentary flavor of the film has been lost and religious motifs, harking back to I Confess, take over. The Kafkaesque nightmare of reality that Hitchcock has maintained has turned into a moralistic question.” -Robert A. Harris & Michael S. Lasky (The Films of Alfred Hitchcock, 1976)

It is high time for the film community to re-evaluate this neglected film. If any other director had tackled the same material in the same manner, it would be considered a masterpiece of the genre. This is a bold statement about a bold film that deserves fresh analysis.

The Presentation:

4 of 5 MacGuffins

The disc is protected in a standard Blu-ray case with film related artwork. This artwork seems to utilize vintage promotional material (though it isn’t the same artwork used for the film’s original one sheet).

The menu utilizes the same art that is on the cover, and it is accompanied by music from Bernard Herrmann’s score for the film.

There is absolutely no room for complaint about Warner’s presentation. Everything really looks quite fabulous!

Picture Quality:

4 of 5 MacGuffins

Black and white cinematography has the capacity to look truly incredible in high definition, and Warner Brothers has offered up a transfer that successfully demonstrates this. The image showcases a lot of fine detail with very nice contrast. The rich blacks do not crush detail, and there is a fully rendered range of greyscale between this and the white. This is a good thing, because much of the film takes place in darkness. There is a healthy layer of grain that betrays the film’s celluloid source, but many film buffs will see this as a good thing. It is certainly preferable to overzealous DNR. There doesn’t seem to be any distracting digital anomalies, but there is some hyperactive grain fluctuation on occasion. This is the single flaw in an otherwise lovely transfer.

Sound Quality:

4 of 5 MacGuffins

The English 2.0 DTS-HD Master Audio is also quite nice, although many modern viewers might wish for a more robust soundtrack. Dialogue is consistently crisp and clear, and this is married with well rendered ambience and intelligible sound effects. This is important, because Alfred Hitchcock uses sound in very interesting ways. The sounds are realistic and draw viewers into the world of Manny Balestrero. It is nice to see that the sound transfer doesn’t interfere. Bernard Herrmann’s jazz-influenced score is given adequate room to breathe for a 2.0 mix, but there may be a few moments in the film that could use a bit more room. Overall, this is an excellent sound transfer for a film that was made in 1956.

Special Features:

3 of 5 MacGuffins

Guilt Trip: Hitchcock and The Wrong Man – (SD) – 00:20:19

Laurent Bouzereau’s Guilt Trip isn’t comprehensive enough to qualify as a “making of” documentary, and this is somewhat disappointing when one compares it to the excellent documentaries that he prepared for Hitchcock’s Universal films. Paul Sylbert (the film’s art director) offers viewers a minimal amount of general information, but this information is always quite interesting. Bouzereau expands on this information by utilizing interviews with Peter Bogdanovich, Richard Schickel, Robert Osborne, and Richard Franklin. These gentlemen offer their general thoughts and feelings about the film, and this adds small doses of insight to the proceedings. This is certainly superior to the usual EPK nonsense that appears on most Blu-rays. Hitchcock fans should be happy that it has been carried over from the 2004 DVD release.

Theatrical Trailer – 00:02:35

The theatrical trailer for The Wrong Man is narrated by Alfred Hitchcock himself (as many trailers for his later films would be). It is certainly more interesting than many trailers, and it is wonderful to have it included on this disc.

Final Words:

The Wrong Man is a seriously underrated gem that deserves to be studied and discussed. This new Blu-ray edition of the film is the best way that fans can see this film on any home video format, and it comes highly recommended.

Review by: Devon Powell

SOURCE MATERIAL:

Herbert Brean (A Case of Identity, Life Magazine, June 29, 1953)

Unknown Author (Balestrero’s Nightmare, Life Magazine, February 01, 1954)

Unknown Author (The Wrong Man, Harrison’s Reports, December 22, 1956)

Unknown Author (Hitchcock and A New Form of Film Suspense, The Times, February 25, 1957)

A.H. Weiler (New Format for Hitchcock, New York Times, December 24, 1956)

François Truffaut (Cahiers du Cinéma, 1957)

François Truffaut (Hitchcock/Truffaut, 1966)

Robert A. Harris & Michael S. Lasky (The Films of Alfred Hitchcock, 1976)

John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock, 1978)

Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Mark Osteen (Hitchcock and Adaptation, 2014)