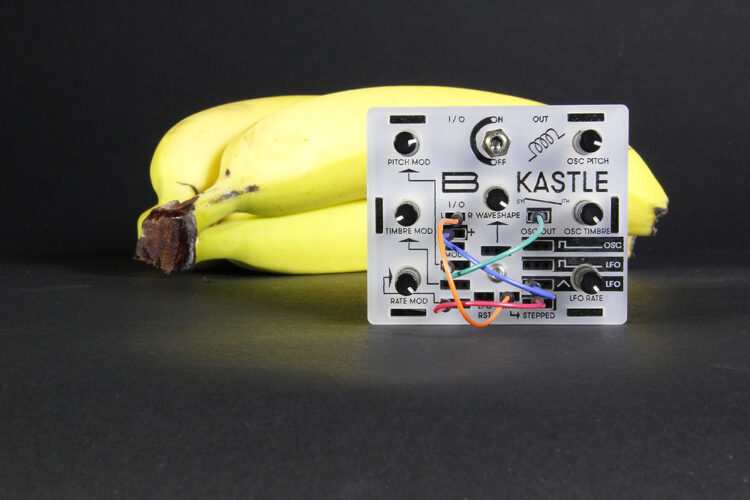

Bastl Instruments’ miniature modular really is very, very small indeed.

Even in a world where toy-like synthesizers are becoming common, the Bastl Instruments Kastle is tiny. It’s not a lot bigger than the recess provided for the three AA batteries (not included), yet the Kastle is capable of phase modulation, phase distortion and something named ‘track and hold modulation’. It is shipped with a set of the tiniest patch cords you’ll ever see to test both your dexterity and eyesight. It’s certainly intriguing, challenging and unusual — but is it fun?

An Englishman’s Home…

With its seven knobs and prominent on/off switch, the Kastle seems to be a simple enough device. Its plastic sides are etched with patterns that are unique to each one and at just 66 x 56 mm it even looks petite when placed next to a Korg Monotron or Teenage Engineering Pocket Operator. Even so, the construction is solid and chunky.

There’s no option to run off mains power and, apparently, batteries are not included for environmental reasons. Possibly there’s a similar justification for the lack of a compartment door, but although the underside of the case is left open, the batteries are held tightly in place and are in no imminent danger of falling out.

Unlike many reduced-scale designs, the knobs do at least have a white position line and they respond well enough, even to subtle tweaks. If you really wanted to you could cap them, but somehow the ‘finger pinch’ action seems appropriate, especially given the even more intricate manoeuvres you’ll have to master to successfully connect those patch cords.

The 36 patch points are grouped in normalised twos and threes, which, to my fading eyesight, would have been more friendly if set in a different colour of plastic. For example, I’m pretty sure I could have located the connection holes more reliably had the background been white. It would also be quite a stretch to describe the 10 tiny wires as robust. Gentle application of pressure is essential if you’re to avoid bending them, but even at my most careful, I still felt as if I were solving a child’s puzzle half the time rather than interacting with a musical instrument. That said, with patience and the occasional need to pull everything out and start over, I coped.

The rear of the Kastle offers just two mini-jack sockets for audio output and CV I/O. Naturally the connectivity opens up wider realms of sonic exploration; you can even draft in other studio equipment, in a limited fashion. The Kastle has a pair of mini-jack sockets, one of which is the (mono) audio output, but the other is a CV I/O port. This stereo mini-jack is routed to the L and R sockets on the front panel. These are the means of bringing signals (of 0-5V) from your modular and routing them within the miniature patching system — or piping some of the Kastle’s own sources to the outside world.

The rear of the Kastle offers just two mini-jack sockets for audio output and CV I/O. Naturally the connectivity opens up wider realms of sonic exploration; you can even draft in other studio equipment, in a limited fashion. The Kastle has a pair of mini-jack sockets, one of which is the (mono) audio output, but the other is a CV I/O port. This stereo mini-jack is routed to the L and R sockets on the front panel. These are the means of bringing signals (of 0-5V) from your modular and routing them within the miniature patching system — or piping some of the Kastle’s own sources to the outside world.

Synthesis

This is an obvious contender for smallest patchable battery-powered modular synth yet made, and as with all modulars, almost any connection can yield interesting results. For traditional I/O, the panel helps you differentiate between the inputs and outputs: outputs are marked with a black rectangle. Fortunately, no damage will occur if you plug randomly — indeed you’re encouraged to do so, which I did regularly, although not always on purpose.

When you power up, a green LED shows through the front panel flashing at the LFO rate. With no connections made, the synth’s complex oscillator emits a constant drone, its pitch set by the Osc Pitch knob in the top right-hand corner. The knob labelled Osc Timbre serves as a modulating (audio rate) oscillator and there’s an LFO ready to be patched in for familiar low-frequency action. In addition, a square wave is available at all times. This can either be combined with the complex oscillator’s output to add extra presence or used as a modulation source.

Three knobs on the left-hand side act as attenuators for any pitch, timbre and LFO rate connections you make. This leaves just the central knob — Waveshape — which acts as a pulse-width control for the square wave output, but has different functions depending on the synthesis mode selected. Its modulation input is situated directly beneath.

The default synthesis mode with no patch cords present is Phase Modulation. Signals received at the Mode input can override this — dynamically too, if you feed in changing voltages such as the LFO output. A high input switches the mode to Track & Hold, whereas low translates to Phase Distortion. To predictably enable either mode, there are handy high/low outputs available, marked ‘+’ and ‘-’ on the panel.

But what, you’re probably wondering, does each sound like? Well, Phase Modulation is a variant of FM synthesis with just two sine wave operators. In this, the default mode, the timbre knob sets the frequency of the modulator leaving waveshape to control the modulation depth. All the Kastle’s tones are decidedly lo-fi, so you shouldn’t expect anything resembling the clean and sleek FM as popularised in the 1980s. Instead, the raw tonality is brimming with buzzy, wobbly cross-modulation as impure as it is attention-grabbingly filthy. It’s FM but not as we know it.

Phase Distortion was Casio’s answer to Yamaha’s DX range of synths. Here it is represented by two sync’ed ramp oscillators each with a wide tuning range. The waveshaper contributes an approximation of high-pass filtering. The end results tend to be somewhat nasal but the lowest pitches cover an array of interesting clicks and farts. Ringing harmonics and vocal tones a-plenty materialise as you to raise the pitch of both oscillators; with high waveshaper values and manipulation of the Osc Timbre knob, the Kastle produces highly convincing formant sounds.

Track & Hold was a new type of synthesis to me. In it, the main sine wave oscillator is sent through a comparator to generate a variable-width pulse wave. This wave gates a track & hold circuit through which the other oscillator passes, but only when the pulse is high. The waveshaper controls the pulse width and the other two knobs set the frequencies of each oscillator. The audible effects are of a glitchy, intermittent wail, yet more clicks and blips, modem noises, credible impressions of short-wave radios, static, jarring ring modulation and grumbling drones. In this mode especially, the Kastle could be a great source of external modulation.

The onboard LFO produces simultaneous triangle and square outputs, with the latter useful for synchronising external modules. The LFO’s reset input is interesting too: it resets the phase of the triangle wave to the highest part of its output. Therefore at slow rates and by applying an external trigger to the reset input, you can mimic a decaying envelope or sawtooth modulation source. Additionally, the LFO may be subject to external rate modulation: you can patch in its own output, which is always a good way of generating less predictable movement.

Probably the coolest modulation source is the Stepped Generator. Inspired by the Rungler Circuit of Rob Hordijk, this delivers voltage patterns that vary depending on connections made at the Bit Input. With no input present, a 16-step pattern is produced. Patching in a high input results in a totally random pattern while a low input generates an eight-step pattern. Best of all, the non-random eight- and 16-step patterns are scrambled every time you patch, but after scrambling they repeat predictably. This has advantages for anyone using the Kastle as a resource for sampling: simply have the Stepped Generator drive waveshape, timbre or pitch and you’ll get something interesting more often than not.

Of course at this scale it’s impossible to cover every avenue. For example, the Kastle doesn’t have an envelope, so if you use it stand-alone, it tends to be a bit of a wailer. Not that this is necessarily a complaint. It’s pleasantly surprising how many variations of noise-ridden digital drones there are, not to mention random and semi-random note patterns and chuntering sound effects all ready for external gating, looping or sampling.

Conclusion

Making gear as small as possible is currently in fashion and sometimes you have to wonder how far it will go before we’re employing nanobots to play for us and a microscope to watch it happen. I remember being overjoyed by Korg’s Monotron series, yet I couldn’t tell you the last time I put batteries in mine. The Kastle is a rather different proposition to Korg’s trailblazers, though, and a more complex beast generally. Wholly digital in nature, its three types of synthesis have much to offer, assuming you have an appetite for gritty, crunchy lo-fi.

Should the novelty for buzzy digital tones ever wear off, the Kastle could still earn its keep as a neat extra sound and modulation source for your modular or other synth. Similarly, it might be good raw material for sampling, maybe in a battery-powered rig based on Bastl’s own Microgranny 2 or Korg’s Electribe Sampler or Microsampler.

My only issues were with the patch cords, specifically their size: I often felt the need to venture out into sunlight armed with a pair of tweezers to use them properly. Strangely enough, even this irritation had a spin-off benefit. Returning to my Eurorack system after playing with the Kastle for a while, suddenly everything felt spacious, which is a new experience.

The Kastle is Open Source and also available as a kit, plus there are options to swap out the Oscillator and LFO chips. If you’re willing to invest time and effort, it therefore has more to offer. For many of us, I suspect it’ll be primarily viewed as a source of weird noises and aliased drones you can whip out of a pocket whenever the urge arises. At the price, there are plenty of reasons to justify owning one.